Medical tubing is made from several types of plastic, including polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene, thermoplastic elastomers (TPE), nylon and silicone. Traditionally, PVC is most widely used, because it bonds easily with other plastics. Non-PVC tubing is often more difficult to bond, because chemicals don’t react as quickly or as efficiently.

“PVC is generally easy to bond with adhesives, but care should be taken to understand potential plasticizer migration,” warns Christine Marotta, medical focus segment manager at Henkel Corp. “We have developed simple processes to screen flexible PVC bonds to measure the impact of such migration.

“Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) and polyurethane (PU) are also readily bonded with select adhesive chemistries,” adds Marotta. “Although polyolefins can present challenges, achieving high adhesive bond strengths (including substrate failure) is possible with select adhesives and some simple surface preparation techniques (priming with cyanoacrylates, plasma or corona treatment with other chemistries).”

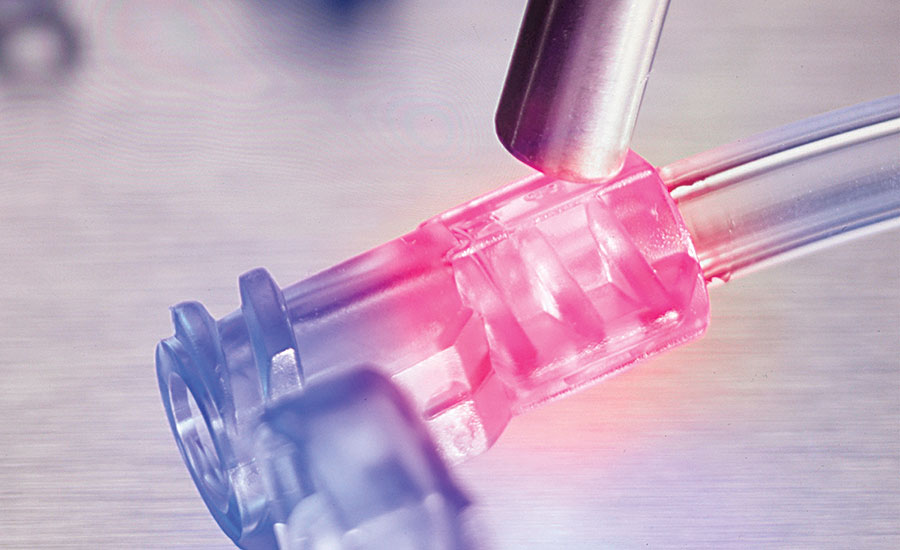

Marotta says silicone tubing is also readily bonded-particularly with silicone adhesives, but also with cyanoacrylates. The mating component materials common to medical tubing, such as polycarbonate, acrylic, rigid PVC, metals and elastomers, are also easy to bond. “This ensures a tight connection and the critical sealing,” Marotta points out.

According to Kyle Rhodes, market manager for the Americas at Elkem Silicones, PVC and urethane are generally easy to bond to with a urethane- or acrylic-based adhesive. “These materials have very compatible chemical groups on the surface, which react well with vinyl groups within the adhesive, and create a very strong bond, often stronger than the plastic tubing,” he explains.

“Short chain Nylon 6 or Nylon 6,6 are very common,” adds Rhodes. “Soft copolymers like polyether block amide (PEBA) are also common, and found in many applications throughout the medical device industry. Silicone medical grade tubing is also common, and best bonded with a one- or two-part silicone adhesive.”

However, some materials are more of a challenge to bond, such as polyethylene and polypropylene. “These polymers have a very simple repeat chain of C-C for a backbone with very little bondable groups on the surface,” claims Rhodes. “Surface treatments like plasma, corona or flame treatment add reactive groups onto the surface, and allow for high-strength bonding with various adhesives.

Rhodes says other materials, such as fluoropolymers, teflons and long-chain polyamides like Nylon 24, are more difficult to bond to, even with surface treatment. “Fluoropolymers contain a chemical group which repels typical adhesives away from the surface, and keeps them away by physically blocking access to the reactive groups at the surface,” he explains. “Bonding to silicone medical grade tubing is very common with silicone adhesives, but is a challenge for carbon-based acrylics and urethanes.”

“Polyolefins such as polypropylene, polyethylene and acetal are the most challenging to achieve high bond strengths,” adds Marotta. “Chemically, these materials are comprised of simple carbon-hydrogen chains yielding little functionality for an adhesive to grab onto and achieve a strong bond. Additionally, they generally possess very slick or waxy surfaces [that are] not conducive to surface wetting of the adhesive.”

Fluoropolymers possess similar characteristics to olefins-low functionality and slick surfaces. Marotta says these bond challenges can be overcome with simple surface preparation techniques, such as priming or treatment.

Plastic Tubing Bonding Tips

Encompass UV-cure acrylic urethane adhesives incorporate Ultra-Red fluorescing and See-Cure color-change technologies. The adhesives are blue, but become colorless when cured and appear red under low-intensity black light during inspection. Photo courtesy Dymax Corp.