While the concept of noncontact might seem to be out of place at an ammunition factory, it actually fits very well there for certain assembly processes, such as

Jump to: |

sealing bullets. Nearly three years ago, several of the largest U.S. ammunition manufacturers were looking for a way to automate the process, make it less hazardous and improve sealant performance. The manufacturers met with several dispensing equipment and material suppliers, including Hernon Manufacturing Inc.

Since the 1940s, assemblers used their fingers to apply a thin coating of asphalt inside the bullet’s mouth casing prior to the insertion of gun powder and the bullet. The major problem with the process is that manufacturers had to wait 24 hours for the asphalt to dry before completing the assembly. Equally problematic was that the asphalt often failed and the bullet did not pass the leak test.

Since 2010, these manufacturers have used an automated dispenser to apply a very thin adhesive to seal each bullet. The SS3500 dispenser from Hernon is stationary and shoots a 0.5-microliter dot onto each bullet as it passes underneath. Capillary action causes the dot to disperse around the bullet.

The Ammunition Primer Sealant 59621 (also from Hernon) is based on an acrylate ester. Because it has both ultraviolet and anaerobic cure mechanisms, it cures within 3 seconds. It is available in red, green and clear for usage identification. These sealants are used by the U.S. military, police departments and FBI.

“This dispenser seals more than 280 bullets per minute and requires just 1 liter of sealant to seal 1.4 million 5.56-caliber primers,” says Harry Arnon, president of Hernon. “It is about the size of a matchbox, but features a circuit board that allows it to be easily programmed and extremely precise.”

Fluid Terminology

Definitions are intended to clarify words and phrases. However, some phrases are not so easy to define. For example, suppliers of dispensing equipment and materials say there is no industry-standard definition of “thin material,” although they acknowledge that certain materials tend to be considered as thin. Some suppliers say thin materials can have a viscosity as high as 5,000 centipoise (cps), while others say it should be as low as 300 cps.

“The term ‘thin’ depends a great deal on the material as a point of reference,” says John Lafond, technology manager for instant adhesives at Henkel Corp. “For many adhesives, a viscosity of 750 cps is considered thin. Cyanoacrylates (CAs) with the same viscosity would be considered midrange. I consider thin cyanoacrylates to be those under 500 cps.”

CAs are one-component acrylic resins often referred to as instant or super glues. Their viscosity can range from watery (2 to 5 cps) to non-sagging gels, which typically have a viscosity of more than 10,000 to as high as 300,000 cps.

Many manufacturers, such as those that produce medical devices, like the quick-curing characteristic of CAs. The companies also like that the material bonds within 5 to 20 seconds, can reach a holding power up to 3,000 psi, and bonds better when very little is used. Another benefit is that water-thin CAs can be used to fill very narrow gaps between assembled components.

On the negative side, CAs are brittle, have low shearing strength, can irritate the skin and eyes, cannot be used on glass surfaces, and require a clean surface and delivery system during dispensing. They also are subject to blooming, which is the formation of a white haze or powdery residue that forms near the bond when vaporized CA monomers settle to the surface. Blooming does not affect performance, but can be a problem for manufacturers who immediately package devices after assembly.

The key to effectively dispensing CAs is dry equipment. Even a trace amount of water will initiate curing.

“The key to effectively dispensing CAs is dry, dry and dry, as the smallest trace amount of water will initiate curing." |

If necessary, manufacturers should use an air regulator and one or more air driers to create a dry-enough delivery system and work environment.

Other popular thin materials include adhesive activators, coatings (conformal, emulsion and water-based), epoxies, adhesives (anaerobic, methacrylate and UV-curable), oils, alcohols, liquid fluxes, reagents, acrylics, inks, paints and solvents.

The viscosity and uses of these materials vary greatly. For example, adhesive activators have a viscosity of 10 to 100 cps and are designed to increase cure speed and improve bonding. Automakers often apply an activator (by spray) to strip moldings to increase adhesion.

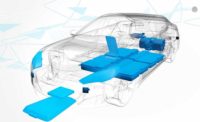

Conformal coatings have a viscosity of 2,000 to 5,000 cps and are primarily used to protect electronic assemblies from dust, dirt, abrasion, moisture and mechanical stress. Liquid fluxes have a viscosity under 1,000 cps, and they help solder cling to metal by removing oxide buildup. Matt Connell, an application specialist at Nordson EFD, says flux is often used when soldering automotive HVAC systems.

Medical device manufacturers often use solvents such as cyclohexamene and methylethylketone, both of which have a viscosity below 50 cps, to coat catheters. Acetone, another solvent, is extremely thin, at 0.324 cps, which makes it very flammable. Despite this negative attribute, acetone is very effective for solvent-welding acrylic parts.

Material Challenges, System Solutions

For the most part, thin materials present the same dispensing challenges as thick materials: dripping, clogging, inaccurate shot placement, and inconsistent and inaccurate shot size. The one exception is cyanoacrylates, which also require a completely dry delivery system to prevent the material from curing before it can be dispensed.

Regardless of system used—manual, semiautomatic or fully automatic—the key to preventing these problems is to use the right syringe (manual or semiautomatic systems) or valve (automatic systems).

Manual systems are self-contained and portable. Most feature a plastic syringe in a pistol-grip dispenser. The syringe is pre-filled with material and has a tip (or needle) at the end. When the assembler squeezes the trigger, pressure is applied to the syringe plunger and material is dispensed.

Inconsistent shot size and syringe leaking are the most common problems associated with manual systems. Inconsistent shot size can be avoided by using a syringe that’s properly tapered or has a connected tip that’s properly tapered. If it’s tapered too much, shot size can decrease as the material repeatedly moves to the tip orifice. The syringe should also have a tight-fitting plunger so material does not leak at the top, air bubbles don’t form and full pressure is applied to the material during dispensing.

Henkel makes the Model 1506477 manual system, which uses a peristaltic pump to feed material from a bottle to a dispensing tip via a thin tube. This system is specifically designed to dispense precise and repeatable shots of CAs without clogging. The system can be used with CAs up to 1,500 cps and dispense material drops from 0.002 to 0.009 gram. It has six shot size settings and uses 1-ounce bottles of CAs.

Semiautomatic systems feature a syringe attached to a digital controller. The assembler inputs three dispensing parameters prior to application: air pressure and vacuum, dispensing duration, and tip size. Upon foot pedal or finger-switch activation, pressurized air and vacuum are provided, and material is dispensed through the syringe tip.

The Ultimus V semiautomatic dispensing system from Nordson EFD maintains consistent shot size by allowing the user to enter trigger points for pressure, time and or vacuum settings. Assemblers only need to program the controller once for each fluid and job. The system displays all dispensing parameters to simplify process control.

An auto increment mode adjusts dispensing parameters after a certain number of shots or a specified lapsed time. The Optimeter accessory increases airflow as the syringe empties, providing users with greater material control. For higher-volume applications, the system can be connected to a benchtop robot.

Fully automatic systems use a valve, in conjunction with a controller, to perform very accurate, high-volume material dispensing. The systems feed material to the valve from a reservoir (pail, bottle or syringe) using either a pressure-time or peristaltic-volumetric method.

The pressure-time method involves applying pressure either to a cylinder that moves the material or directly onto the material to move it through a tube. In contrast, the peristaltic-volumetric method uses peristaltic pumping action to move a preset volume of material.

Diaphragm valves are frequently used to dispense CAs and other thin materials. Needle, spray and jetting valves are used to dispense non-CA thin materials. All of these valves require a narrower orifice and use less air pressure than those used to dispense thick materials.

“When dispensing CAs in particular, manufacturers should not use valves with metal wetted parts,” says Can La, product manager for Techcon Systems. “All parts that contact the material should be made of moisture-resistant material such as polypropylene, polyethylene or Teflon to prevent premature curing of CA.”

Connell says valves with passivated steel components can be used to dispense CAs. Passivated stainless steel has no free iron, which can negatively react with CAs and cause clogging.

The VD510 diaphragm valve from Fisnar Inc. features an adjustable stroke to fine-tune shot size. During dispensing, an air pressure signal forces the valve’s diaphragm to pull back and create an opening for the material to flow through. The valve is suitable for robot integration, has a maximum flow rate of 0.3 liter per minute, and can deliver shots as small as 0.001 cc.

Needle valves are preferred for microshot dispensing of nonvolatile materials because they sit in the tip adapter and eliminate dead fluid between shots. Spray valves cleanly dispense an even coat of material exactly where it’s needed, minimizing waste and cleanup. Manufacturers use spray valves to apply adhesive activators, inks, reagents and coatings.

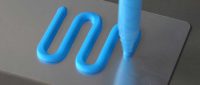

Jetting valves, like the TS9000 from Techcon Systems, offer positive shut-off and only need to move in the X and Y axes, which saves time. The TS9000 is a noncontact valve capable of dispensing 350 shots per second, with a repeatable microdot size as small as 2 nanoliters. It has a nozzle orifice diameter range from 0.07 to 0.4 millimeter.

Not all fully automatic systems use valves. For example, the syringe-based SmartDispenser system from Fishman Corp. uses air-free linear drive technology to dispense material. Fishman introduced the system in 2003 and the LDS 9000, the latest version, in 2010.

SmartDispenser is a sealed, moisture-free system powered by a stepper motor. An assembler enters specific dispensing parameters and activates the system by a foot pedal or finger switch.

The stepper motor powers a leadscrew, which turns and moves a piston. The piston, in turn, pushes material and dispenses it through a syringe. No air pressure is used.

“The user inputs specific drawback parameters to prevent dripping and clogging,” says Nancy Gleason, vice president of business development for Fishman Corp. “Back-off steps are entered based on the application and fluid viscosity for optimum performance. Suck-back, which is used by valves, is often ineffective. It has no adjustment.”

The system also features a process control mode, which gradually reduces back-off as the syringe empties. As a result, dot size repeatability is ± 2 percent.