While visiting a Russian manufacturing facility in 1978, John Carter was again faced with the challenge of finding a better way to dispense adhesives.

Several years earlier, in 1972, his company, EFD—Electron Fusion Devices, developed an automatic fluid dispenser, the 1000V-100. This dispenser used adjustable air pressure to dispense shots of material. It relied on a foot pedal to regulate dispensing speed and determine material amount.

By 1978, EFD was well-known for making quality dispensing systems, and the Russian plant manager invited Carter to tour the facility. There he saw more than 200 workers dispense adhesive through a funnel and use a cork stopper to control the amount dispensed.

A copper wire through the cork was attached to a bent loop around the index finger of the assembler. Deposits were made by lifting and lowering the finger.

Episodes like this one illustrate how far dispensing technology has advanced in more than 50 years. In the early 1960s, commonly used fluids included silicones, epoxies, white glues and cyanoacrylates. From a terminology standpoint, these materials are not much different than those of today.

However, from a standards and performance standpoint, today’s materials are light-years ahead. New high-tech adhesive formulations complement “old reliable” formulations to help manufacturers bond a variety of substrates.

Manufacturers today are also faced with the challenge of producing ever smaller products. They are demanding higher quality and faster throughput, and they are implementing lean and Six Sigma production improvement processes. These factors, along with the need to run automated assembly lines on a lights-out basis, have required suppliers to continually develop better equipment—and a wider range of equipment—to accurately dispense assembly fluids.

Regardless of the production environment, manufacturers need reliable yet simple-to-use components and equipment that ensure process repeatability. Global companies also want dispensing devices that can be easily moved from an R&D lab at corporate headquarters to an operator’s workstation anywhere in the world without affecting productivity.

Quality Through Technology

In the early 1960s, Rhode Island was the costume jewelry manufacturing capital of the world. It produced 80 percent of the costume jewelry made in America. The state still has a prominent position in the jewelry industry today.

A lifelong Rhode Island resident, Carter was a supplier to the industry. In 1963, he developed an electron fusion welding process that enabled jewelers to connect two pieces of metal much quicker than manually applying adhesives with toothpicks or squeeze bottles.

Carter then formed EFD and began selling welding machines to jewelers, who used them to weld earring parts, belt buckles and other metal components. Jewelry sellers preferred electron fusion welding to silver brazing because the welding process cost less and produced better-quality products.

Several years later, Carter looked to expand his business by creating a machine jewelers could use to precisely dispense metal brazing pastes. That machine was the 1000V-100.

More importantly, Carter soon learned that his machine could be used in any industry that required material dispensing. He only needed to slightly modify the machines so they were able to dispense adhesives, lubricants, paints and other liquids.

Over the next 15 years, EFD focused on improving the quality of its dispensers through better valves and controllers. Diaphragm valves were introduced in 1976, followed by spray valves and needle valves in the 1980s. Controllers evolved over the same period.

Unfortunately, the plastic dispensing tips and syringe barrels purchased by EFD from outside suppliers did not improve during this time. So in 1987, EFD began making these components using injection molding.

Within a few years came the consumer electronics boom of the 1990s and the need for manufacturers to produce smaller parts. Assembling these products required even more precise dispensing systems.

One way EFD responded is by introducing the 702 Series mini-diaphragm valve. Manufacturers of optical media (DVDs, CDs, Blu-ray discs) especially like this valve because it applies precise amounts of dyes, UV-cure lacquers and UV-cure adhesives in tight spaces.

Around this time, automakers began looking for ways to improve quality throughout the plant. Several focused on eliminating part deformation in their metal stamping operations. MicroCoat, a noncontact lubrication system developed by EFD in 1996, helps manufacturers achieve this goal while saving millions of dollars in lubricant waste and downtime.

The system applies a consistent amount of fine oil to sheet stock to eliminate slug pulling and increase tool life. It mounts easily to provide controlled lubrication at specific locations.

As the 20th century drew to a close, several industries implemented or increased microscopic manufacturing processes. This evolution makes precision dispensing essential for a wide range of applications—from waterproofing and sealing cell phones, to building automobiles and bonding catheters.

Benefits of Automation

Over the past 20 years, dispensing technology has evolved from benchtop and foot-pedal-controlled equipment, to semi- and fully automated high-performance valves and dispensing robots. Manufacturers have embraced this automation for several reasons.

Automated dispensers are cost-effective and easy to implement. They also increase production, improve quality and reliability, reduce worker fatigue, and provide a cleaner, safer working environment.

The Ultimus V, a semiautomatic dispensing system, maintains consistent shot size by allowing the user to enter trigger points for pressure, time and vacuum settings. Assemblers only need to program the controller once for each fluid and job. The system displays all dispensing parameters to simplify process control.

An auto increment mode adjusts dispensing parameters after a certain number of shots or a specified lapsed time. The Optimeter accessory increases airflow as the syringe empties, providing users with greater material control. For higher-volume applications, the system can be connected to a benchtop robot.

Consistent shot size lowers material cost by reducing fluid waste and overall fluid consumption. This is critical, as some materials, such as silver-filled epoxies, cost several hundred dollars per ounce. Systems that can reliably dispense these expensive materials are critical to a manufacturer’s profitability.

Automated dispensers also prevent material dispensing in the wrong location. When this occurs, part cleaning or rework must take place—both of which lessen productivity, increase cost, and increase the chances of part failure.

Dispensing technology continues to evolve, but there will never be a one-type-fits-all solution for manufacturers. For example, one company with extensive dispensing equipment experience may require systems with the utmost speed and precision. But another company that is just starting to automate their dispensing process may be better served with simpler handheld or benchtop equipment.

The challenge for suppliers like Nordson EFD is to provide products that meet the wide array of manufacturing needs.

Nordson EFD at 50: Looking Backward and Forward

Last year, Nordson EFD celebrated its 50th anniversary. The company and its products have changed significantly over that time.

In 1963, John Carter founded EFD with a few people, and the company’s main technology was electron fusion welding. The company didn’t produce its first dispenser, the 1000V-100, until 1972.

Today, Nordson EFD makes a full range of dispensing products, from tabletop systems to dispensing robots. The company employs nearly 500 people, maintains offices in more than 30 countries, and supports its customers worldwide with a network of local sales and service teams.

Nordson also operates a Web site that is available in 15 languages. Plus, it continues to invest in R&D to develop innovative products that meet new environmental regulations.

“In the early years, our equipment was more pneumatic than digital,” recalls Lorrie Higgins, new product development project coordinator for Nordson EFD. Higgins is a 40-year employee of Nordson and has been involved in all phases of manufacturing and new product development.

The 1000V-100 used adjustable air pressure to dispense material shots. Adjustments were made via a series of knobs, and the device was triggered with a foot petal. There was no digital display.

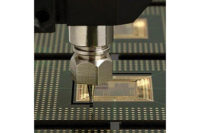

Compare that to the EFD PICO dispensing valve, introduced in 2013. The piezoelectric 500-hertz valve dispenses at speeds of up to 500 cycles per second with dots as small as 0.5 nanoliter. Because it does not contact the substrate, the valve can apply precise amounts of fluid on uneven surfaces or products with small components, tight tolerances or hard-to-access areas, such as mobile handsets.

In addition, the valve controller has extensive memory, enabling operators to immediately call up a program from a past dispensing application. Its digital controls are accurate to ±10 microseconds.

Product development has also changed. Higgins recalls the days when she would simply be told about a new product—and then engineers and floor workers would build it.

“Today, we go through a six-phase Nordson nVision process to determine if the new product is worth developing to truly meet our customers’ needs,” she says. “The six phases take a product from its idea phase through all aspects of its development. A collaborative team from different departments, and even different countries, attend weekly meetings and establish tasks to develop the product, put it through its rigors and complete each phase. I look forward to seeing where the company is headed in the coming years.”

Last year, Nordson EFD ran a promotion to celebrate its 50th anniversary. The promotion offered a new-dispenser credit for the 10 oldest dispensers that customers returned.

Among the trade-ins was an EFD dispenser used by one company for 33 years. It was still in production at the time: applying urethane between a glass globe and a fixture.

“Some of the jobs the old dispenser was used for were very tedious and time consuming,” says Lori Decker, operations project coordinator with EGS—Electrical Canada. “Since switching over to the Ultimus I dispenser, production is 70 percent faster. Our operations team loves the new machine because they no longer feel as if they waste time and struggle to get the job done!”