Designing, assembling and testing aerospace wire harnesses present unique challenges to harness manufacturers.

| Jump to: |

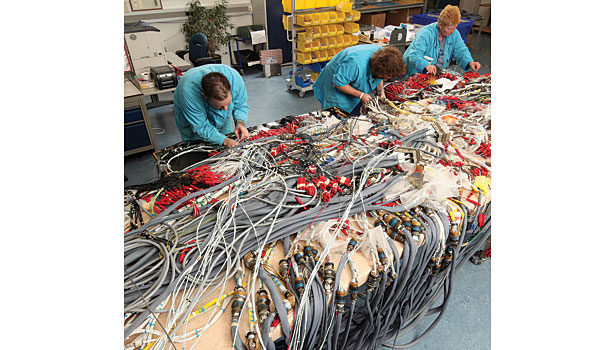

The harnesses are large, heavy and complex. A typical harness might be 40 feet long with hundreds of components and multiple breakouts. Aerospace harnesses must withstand extreme environmental and operating conditions. And, needless to say, they must be extremely reliable.

Successful harness manufacturers thrive on meeting these challenges, but doing so requires a qualified and dedicated workforce equipped with the proper tools and latest technologies.

Day After Day

At 7 a.m. every weekday, 90 assemblers arrive for work at Co-Operative Industries Aerospace and Defense (CIA&D) in Fort Worth, TX. The workers go to their workcells for a morning briefing where that day’s work is discussed and workers voice any concerns or questions. Harness assembly then begins.

Located in a 122,000-square-foot former big-box store, CIA&D has been making wire harnesses for more than 60 years. The company makes thousands of harnesses annually, in addition to repairing thousands more and producing hundreds of ignition leads for aerospace engines.

Prior to 9/11, major aircraft manufacturers had enough capability in-house to disassemble and repair components, including wire harnesses. Since the tragedy, economic factors have forced them to look for ways to reduce costs. One way is to outsource harness repair to companies like CIA&D.

“About 99 percent of the harnesses we repair are made by other aerospace harness manufacturers in Europe or Canada,” says Sam Symonds, president and CEO of CIA&D. “But, we also repair our own harnesses.”

The main challenge for CIA&D assemblers is that they must repair harnesses based on the other manufacturers’ documentation, which must be created by the top assemblers. Sometimes other manufacturers don’t allow extensive repairs, just a ‘check and test.’ As a result, CIA&D staff is asked to develop a designated engineering representative (DER) repair.

Symonds says this requires assemblers to first determine if a harness is even repairable and then write up a component maintenance manual on how to perform the repairs.

“Both steps can be time-consuming, but we pride ourselves on repairing harnesses quickly,” says Symonds. “We staff accordingly so our typical turnaround time is less than 30 days, and airline companies like that. For example, Continental Airlines used to have GE repair their engines and engine harnesses. Now we do the harnesses, and GE installs them and repairs the rest of the engine.”

In September 2012, CIA&D implemented a 9-80 work schedule similar to that of its largest customers, including Raytheon Co., Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. Under this schedule, CIA&D employees work 9 hours Monday thru Thursday and 8.5 hours every other Friday. There is a 30-minute lunch break each day.

Symonds says changing work hours has not affected productivity, but the company saves money on utilities by being closed two extra days per month. Equally beneficial, the company can schedule work on those open Fridays if project deadlines demand it.

International Assembly

Fokker Elmo was established in 1961 specifically to build electrical harnesses and panels. Harnesses are made at manufacturing facilities in The Netherlands, Turkey and China, then sent to OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers around the world.

Most of the harnesses go directly to manufacturers like Airbus, Boeing, Bombardier, Lockheed Martin and Sikorsky. Supplier customers include Alenia (Italy), Aernova (Spain), GKN (UK and USA), Fokker Aerostructures (Netherlands), SACC (China) and Spirit (USA).

Upon being hired, a harness assembler undergoes a two-month training program to learn company practices, says Todd Olson, business development manager for Fokker Elmo USA. After that, he receives specific training for a customer’s harness. Cross-training of assemblers for other wire processing duties is also done as needed.

“When customers provide build-to-print [documentation] with complete engineering information, we use their drawings to create form boards and visual aids, if required,” says Olson. “But, when we’re responsible for the engineering, we use the same CAD-CAM program as the customer. Our proprietary wiring design and manufacturing system enables us to create the harness’s electrical wiring interconnections, maintain complete configuration control and deliver first-time harnesses right and on time.”

Fokker Elmo also maintains a Finish Codes notebook containing the specific assembly process for each type of harness made in The Netherlands, Turkey and China. The codes are translated into Turkish and Chinese for the harnesses made in those countries.

“These codes standardize the process for a specific customer,” says Olson. “From a quality standpoint, our customer should not be able to tell the difference between a harness built in the Netherlands, Turkey or China.”

Standards and Training

Hampshire, IL, and Hermosillo, Mexico, have at least one thing in common: They’re both home to harness manufacturing facilities run by American Precision Assemblers Inc. (APA). The company has been in business since 2002 and employs about 200 people, including 45 harness assemblers.

APA makes thousands of harnesses annually for aerospace OEMs and a supplier that makes interiors for OEMs. The company does not create harnesses with specialty design software. Rather, it uses AutoCAD to make drawings for form boards and Corel Draw for work instructions and visual aids.

All assemblers are cross-trained so they can perform any wire processing job on any assembly line, says Francisco Valenzuela, general manager for APA. General training takes nearly three months, and it follows IPC standards. Additional training is available so assemblers can perform soldering and be certified to the IPC J-STD-001C standard.

“Our main daily challenge is cost control,” says Valenzuela. “In today’s economy, all customers are looking for cost reductions. In turn, we must negotiate better terms with our suppliers and improve our assembly processes. Another challenge is making sure we have proper inventory levels of long-lead-time components to maintain material flow.”

“A Mean Little Devil”

Most of the many thousand harnesses CIA&D workers assemble annually are customized for major aerospace OEMs, like Boeing and Raytheon, and engine makers Pratt-Whitney, GE and Rolls-Royce. Symonds says a little more than half of their harnesses are for the military, including some for helicopters and others for missiles made by Raytheon.

“We make a number of extremely complex harnesses every year. The longest and most intricate one our company ever made was completed last year for an unmanned aerial vehicle now in development. It was a mean little devil.” |

One of the proudest moments in CIA&D history came in December 2012 when the company was named a small business supplier of the year by Lockheed Martin Aeronautics. The award was given in recognition of CIA&D’s development and production support to the F-16 and F-35 aircraft.

“We make a number of extremely complex harnesses every year,” says Symonds. “The longest and most intricate one our company ever made was completed last year for an unmanned aerial vehicle now in development. It was a mean little devil.”

The harness was 40 feet long and had 60 branches, 35 of which fed from one breakout point. All of the branches were braided with electromagnetic shielding and anti-chafing braid material.

“We had eight technicians spend 340 man-hours on the harness,” says Symonds. “At times, all of them were working on it simultaneously. Upon receiving it, the customer placed it on a special jig board for inspection and testing. The harness fit perfectly and worked great.”

Among the most challenging harnesses Fokker Elmo workers ever assembled was one for a commercial airline that turned to Fokker for help when the initial harness supplier couldn’t meet customer deadlines. Assemblers had to build a 3D harness board that allowed them to run the wires and form the bundle in the exact shape it would be installed on the airplane. By meeting the customer’s limited time schedule, Fokker was rewarded with the project contract for that specific harness.

“Our longest harnesses have been more than 100 feet and were used in the fuselage of planes made by several companies,” says Evert Rubingh, senior sales and marketing manager for Fokker Elmo The Netherlands. “The most complex harnesses we’ve made each contained more than 6,000 connection points. They were installed in the airplane cockpit or avionics bay, which is located under the flight deck and houses the plane’s electronic modules.”

Rubingh says testing a harness with 6,000 connectors can take more than 24 hours. Depending on harness complexity, one or more assemblers may be assigned to work on it simultaneously.

In 2011, APA began a special project. It involved assembling harnesses for a company that built cabin suites for the Boeing 777 and Airbus A380 airplanes. The suites were installed in the planes’ first-class section.

“We had to deliver the first harness for inspection in just four weeks, but some of the materials we needed from our vendors required a lead time of 16 to 18 weeks,” says Valenzuela. “It took a lot of coordination between us, our customer and our suppliers to have the first harness finished on time for its preliminary design review.”

The largest harness assembly to date for APA was made for a single-engine jet. Valenzuela says it took 6 hours to build and featured more than 300 components, including wires, terminals, connectors, tubing, braiding and electronic parts.

How Times Have Changed

With 15 years at CIA&D and 35 in the aerospace harness industry, Symonds has seen a lot of changes. In the past, aerospace OEMs would supply a specification to a harness manufacturer requesting a design. Today, the OEMs often design the harness and have the harness manufacturer build it to print.

“Aerospace harnesses are usually very difficult to test and remove at an overnight hangar visit or on the flight line where airplanes are serviced or maintained,” says Symonds. “Portable and computerized test equipment is now used on the flight line to troubleshoot various problems. This eliminates unnecessary harness replacements, thereby saving labor costs and aircraft downtime.”

Assemblers in the engine shop prefer rolling computerized testers, which have custom test interfaces that connect easily to engine or fan case harnesses. Their engine-specific software provides quick and accurate test results. Besides labor savings, the testers ensure each harness meets the manufacturer’s component maintenance manual requirements.

Rubingh cites the introduction of elaborate data bus systems, including fiber optics, as a major change over the past 20 years. These systems are necessary to handle the increased complexity of an airplane’s electrical systems, which feature many more connections. Also important is the FAA’s November 2007 introduction of wiring system regulations that recognize aircraft wiring as a full system.

“Despite all the industry changes, aerospace harness assembly remains a manual assembly process,” says Symonds. “No one has found a way to automate the process because it needs to be done manually. It’s an art.”

Assembly Online

For more information on aerospace harnesses, visit these articles: