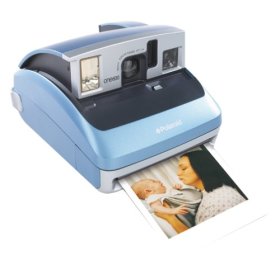

Got one of these? It'll be useless in a few months. Polaroid will stop making film for it this month.

Virtually overnight, the whole process changed. These days, of course, it’s all done on computers: writing, editing, photography, page layout. Better still, the finished page is sent directly to the press.

For me, the worst part of the old method was coating the columns with wax. Inevitably, the sticky stuff got everywhere: fingers, desks, clothes, notebooks, files. I can’t say I miss those days. Still, I often feel a tinge of regret for the folks that made the coating machine. No doubt they did their best to make the finest machine money could buy. But if a technology comes along that helps you do the job better, faster and cheaper, you have to make the switch.

It’s a familiar story in our technological age. Someone invents a mousetrap that’s so much better than the existing mousetrap that the older technology quickly becomes obsolete. The company that made the old mousetrap has two choices: Keep pace with the new reality or join its old product in the dustbin of history. The competition doesn’t care if you’re a household name or a pioneer in your field. You either innovate or you die.

The latest chapter in the struggle between old and new technologies is playing out now in Minnetonka, MN. Earlier this month, Polaroid Corp.announcedthat it would no longer make instant film for its cameras. Thanks to digital cameras, the Polaroid instant camera is about to go the way of the typesetter and the waxing machine. And last week, the companyfiledfor Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection for the second time in its history. (To be fair, the latter is not necessarily related to the former. Polaroid is blaming its financial difficulties on its parent company, the Petters Group, whose founder is currently in federal custody for alleged fraud.)

What a shame it would be if we lost the company that, with Kodak, invented photography. At least Polaroid is trying to keep up, and now offers a slew of products for digital imaging. The company’s newPoGo portable printer, in particular, looks like a winner. The pocket-sized device prints photos from digital cameras and cell phones, without the need for ink or ribbons. The heart of this new gadget is ZINK photo paper, an advanced composite material with embedded yellow, magenta and cyan dye crystals. The printer uses millions of tiny pulses of heat to activate the crystals and thereby create an image. Read about ithere.

What about your company? Are you working on the next PoGo printer in your field? I fear that many U.S. manufacturers are not. After a decade of uninterrupted increases, U.S. investment in research and development is set to fall next year, as corporations and the federal government tighten their belts in response to a faltering economy. After accounting for inflation, total R&D spending in the United States is expected to fall by about 1.6 percent in 2009, according to areportbyBattelle Memorial Institute, a nonprofit trust that does scientific research for the government and industry.

That’s a distinct contrast from recent years. Since the late 1990s, R&D investment in the United States has increased annually at rates of between 1 percent and 2 percent, including inflation.

A similar shift is occurring overseas. Driven by China and other Asian countries, global R&D investment has risen steadily for several years running. In 2009, however, global R&D spending in inflation-adjusted dollars is expected to be flat.

In these tough economic times, many companies go into survival mode, cutting all but the most essential expenses. Justly so. I urge all U.S. manufacturers to consider R&D as one such expense.

Recent Comments

Helpful for Trainees

Cable Assembly Manufacturers

Huawei for manufacturing?

should have a scanner and then 3D print the repair

IPC-A-610 and IPC-j-std-001