Management only wants to invest in production equipment that makes money. To get a capital requisition proposal past the scrutiny of purchasing agents and accountants, the right justification tools are critical. Engineers must convert their technical ideas into dollars and cents. When a document features a detailed cost analysis, it will present your request in terms they understand and help them see the return on investment.

Several analytical methods can be used to justify the purchase of capital equipment. Many large companies have formal procedures that standardize this process. When all the necessary forms are filled out, decision-makers have the information they need to analyze the pros and cons of the requisition.

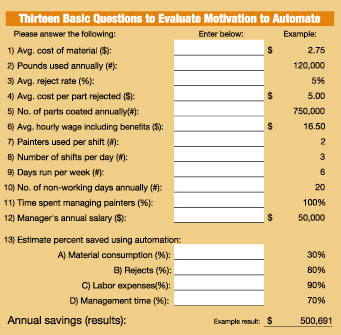

A variety of different philosophies and methods can be used to calculate the potential savings of your proposed assembly equipment. The people who will be reading your capital equipment request will be looking for key factors. If you don't have the comfort of a company-established form to use, your presentation of facts and figures can be an important tool.

According to Dan Bradshaw, business manager at Liquid Control Corp. (North Canton, OH), the details in the form can make an investment make more sense. "The form can relate unit and annual costs to direct and indirect costs, such as materials, direct labor, secondary labor, energy, rework or scrap and other costs," says Bradshaw. "If the justification document only focused on the adhesive and equipment costs, the investment would appear overwhelming. By breaking costs out, you know you will be spending potentially a lot of money, but you see it on a dollar-by-dollar basis, which presents a more complete picture."

Company Objectives

All proposals for capital expenditures should be linked to short- and long-term company objectives. Of course, the equipment will perform functions such as increase production, reduce scrap and rework, reduce lead times, reduce setup times, or offer greater flexibility than the current system or competing systems. These benefits can be cited as means to supporting the company's business strategies, such as increased market share, reduced production costs or faster time to market.The second component of the justification should state the method of attaining these objectives and production goals. This is where the proposed equipment is mentioned, including key specifications. This section can include a statement of important operating principles of the proposed equipment.

The third component should be the estimated capital expenditures. These are the costs incurred before the proposed system actually begins performing production work. These costs can include the following:

- Purchase price.

- Installation.

- Power, electric and air connection costs.

- Tools and fixtures.

- Personnel costs related to acquisition and project management.

- Site preparation and clearance.

- Costs related to removing current equipment to make room for the proposed equipment. If there is the potential for gains from the equipment being replaced or removed due to salvage or resell, these can be deducted from the total costs.

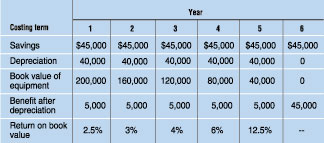

The benefits are the next section of the justification document. Here you will state the net revenue gain that will be generated by the proposed capital expenditure. The benefits can be stated in terms of reduced costs, increased sales or both.

An increase in sales in dollar volume resulting from the use of the proposed equipment may be due to increased production volumes or higher sales receipts without any significant change in production volume. This happens when the proposed equipment reduces scrap work, allowing the company to now offer premium quality products at a higher selling price.

If the focus is on reduced costs, savings can be listed, along with any assumptions made about output levels, operating efficiency and key inputs to the proposed equipment.

The final component will include the life-cycle expectations of the project the capital equipment will support. You may also want to include a timeline to illustrate the length of time needed to implement the actual buying, installing and testing of the equipment before beginning actual production.

Supporting Checklist

Creating the justification form requires some investigation and calculations by the person making the requisition. According to Paul Lowe, author ofInvestment for Production(John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York), a checklist can be very useful. Questions to answer include:- Are you confident the supplier has the proven capacity and reputation to supply and support this capital equipment?

- Does the equipment exactly meet your specifications? If not, what could be the potential operational implications and subsequent costs of this fact?

- Is the proposed equipment proven in the industry? Is any technology used in the equipment on the verge of becoming obsolete?

- Does the quote from the supplier include costs for the following items: transport, insurance, installation, operator training and backup support, such as guarantees, servicing, instruction manuals, spare parts and special tools? If not, you need to obtain the costs for these considerations.

- What is the definite delivery date required and what are the ramifications if there is a delay in the delivery? Make sure you account for different delay scenarios. For instance, what would happen if there is a 1-week delay? What if there's a 4-week delay?

- What if there's a 6-week delay?

- What are the life-cycle costs for this capital equipment? These costs include operational costs, such as labor, material and utility costs; maintenance costs, such as labor, material, parts and inventory; and downtime--should the equipment breakdown, what can be the resulting costs?

Working Capital

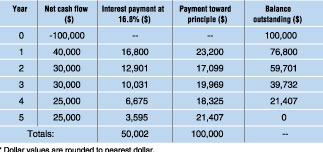

Initial capital expenditure refers to the purchase, installation and all other activities that prepare the equipment for production work. Working capital refers to the costs and benefits that are related to using the proposed equipment during production.While increased throughput is an important factor, it is not the only one needed to justify the purchase of a piece of equipment. Formulas should compare variable and fixed expected costs and benefits associated with the proposed capital investment to the current working practices.

"You can derive a formula to calculate the costs and benefits of just about any type of capital equipment," says Al Harlow, executive vice president of ARTomation (Cleveland). It's important to calculate and analyze direct labor cost, indirect labor cost, materials cost, scrap cost and quality cost.

Direct Labor Cost

"Traditionally, labor replacement and quality assurance have been the primary reasons for investing in more sophisticated systems," notes Harlow. "When calculating labor savings, many assume a robot will replace one human doing the same amount of work. This is rarely the case."

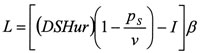

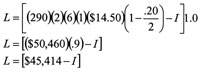

For instance, in a manual adhesive application or painting operation, the operator may turn equipment off and on, wield an applicator gun, and monitor air pressures or power settings. Harlow recommends using the following formula to calculate annual labor costs or savings:

Indirect Labor Cost

"A common mistake is not budgeting for an increase in indirect costs due to implementing automation," warns Harlow. This can include the time required to perform scheduled routine maintenance or program a piece of automated equipment.

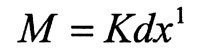

"Programming a system using a teach pendant for each new part while the line sits idle can be very expensive," notes Harlow. "If several program files are necessary, this aspect of indirect labor can be high." If this labor cost is unacceptable, you may want to opt for a system that is easy and fast to program or that allows off-line programming. If you are comparing systems, Harlow suggests looking for equipment with the least amount of indirect costs associated with its operation and maintenance. He recommends the following formula:

Materials Cost

Material costs should include direct materials--those used for production purposes--and indirect materials, such as refrigerants, lubricants or cleaning fluids. "You may want to look at productivity and cost savings that are possible when buying larger inventories of materials," explains Liquid Control's Bradshaw.

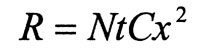

For an adhesive application, the material consumption per year requires calculation of the volume of adhesive required for the joint and annual production levels:

This formula, originally proposed by Harlow and featuring further clarification by Kevin H. Bryant, P.E., a Dix Hill, NY-based consultant, requires some up-front analysis. Previous experience with the process and equipment are important for more accurately determining the material savings possible with the proposed capital purchase.

Potential savings can come from reduced consumption due to more accurate placement of adhesives, fewer dropped or damaged fasteners, or elimination of fasteners altogether if the assembly design now incorporates tabs and slots rather than mechanical fastening methods.

Scrap and Quality Cost

Don't forget to include the costs and potential savings associated with quality issues. The cost of poor quality includes yield losses, rework charges, returns, repairs and lost business due to unhappy customers. Quality costs that can add value in the long run include those related to training, quality audits and statistical process control activities.

As most engineers know, quality is difficult to measure. The savings benefit, if recognized, can be a viable justification factor. "When you reduce the costs of quality, you improve quality, increase productivity, shorten cycle times and develop loyal customers," says John Kane, president of Acu-Gage Systems (Manchester, NH).

- Material handling and freight costs for shipping to and from a repair house or customer.

- Rework.

- Inspectors.

- Costs associated with expediting rework to meet delivery dates.

- Part sorters.

- Part or assembly recertification.

As with the proposed savings in material consumption, the percentage decrease in rejects requires an estimate by someone with experience with the process, product and equipment. This may require participation from the equipment supplier, other assembly engineers and design engineers.

Executive Summary

Most senior executives only appreciate capital equipment and assembly technology if it makes products better or less expensive. They value product cost and quality above technical wizardry.An executive summary can be a very helpful tool in getting a sign-off on new equipment. In fact, it's the only section of a capital equipment justification report that is likely to be read by everyone involved in the decision-making process. The following tips will ensure that your proposal receives serious consideration:

- Keep it short. Three or four paragraphs are sufficient. Remember that senior executives are very busy and often pressed for time. Clarity, focus and brevity are critical. Keep technical content to a minimum.

- Identify a real need or problem faced by your company or division. Remember to think strategically and capture management's attention. Explain how the capital equipment will have a positive impact on the bottom line.

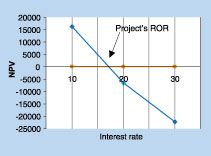

- Identify costs. Address key issues such as payback time and rate of return.

- Quantify the benefits. Account for tangible returns, such as increased productivity and reduced costs. Estimate the intangibles, such as improved safety and increased flexibility.

- Quantify the costs. Add up initial costs, such as installation and training. Estimate the ongoing costs, such as maintenance and upgrades.

Also remember that every company, regardless of size, has various departments competing for the limited amount of capital that it has. Your proposal must look better and make more financial sense than all the others.