Once upon a time, International Harvester Co. was the crown jewel in Chicago’s robust industrial landscape, which included such other gems as the Crane Great Works, General Motors Electro-Motive Division, Pullman Calumet Works, U.S. Steel South Works and Western Electric Hawthorne Works.

This year marks the 175th anniversary of International Harvester’s first factory in Chicago and the 150th anniversary of its legendary McCormick Works, which was called “the world’s largest farm machine factory.”

For more than 100 years, the company was synonymous with manufacturing in the Windy City. Its factories mass-produced millions of threshers, tillers, tractors and other products that were used by generations of farmers.

Humble Beginnings

After inventing a mechanical reaper in Virginia in the early 1830s, Cyrus McCormick set up manufacturing operations in Chicago in the late 1840s to be closer to his customer base of prairie farmers. At the time, Chicago was a small town with a population of only 20,000.

McCormick secured financial backing from William Ogden, the first mayor of Chicago who also built the city’s first railroad, the Galena & Chicago Union. McCormick’s younger brother, Leander, was put in charge of running the fledgling operation.

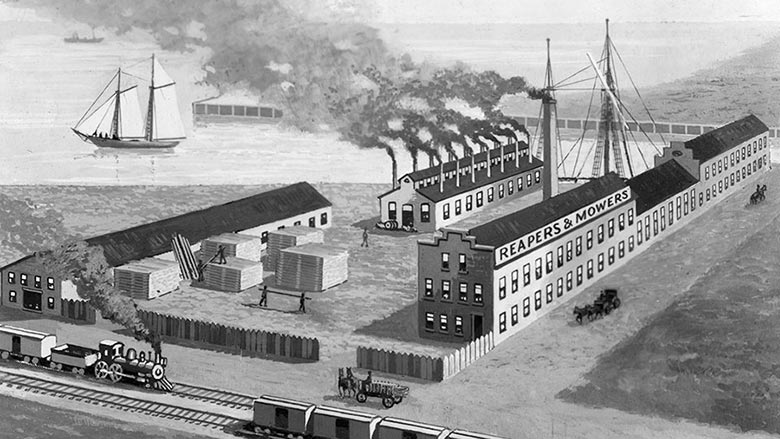

The company’s first factory was located on the north bank of the main branch of the Chicago River, near where the DuSable Bridge crosses Michigan Avenue today in the fashionable Streeterville neighborhood.

The two-story wood-sided building was 100 feet long by 30 feet wide. It featured a 10-horsepower stationary steam engine for driving machinery, such as lathes, planers and saws. Inside, carpenters made wooden frames, while other workers forged, hammered, drilled and riveted metal parts by hand. Within a year, the McCormick Reaper and Mower Works employed 33 men, including 10 blacksmiths, who produced 450 machines.

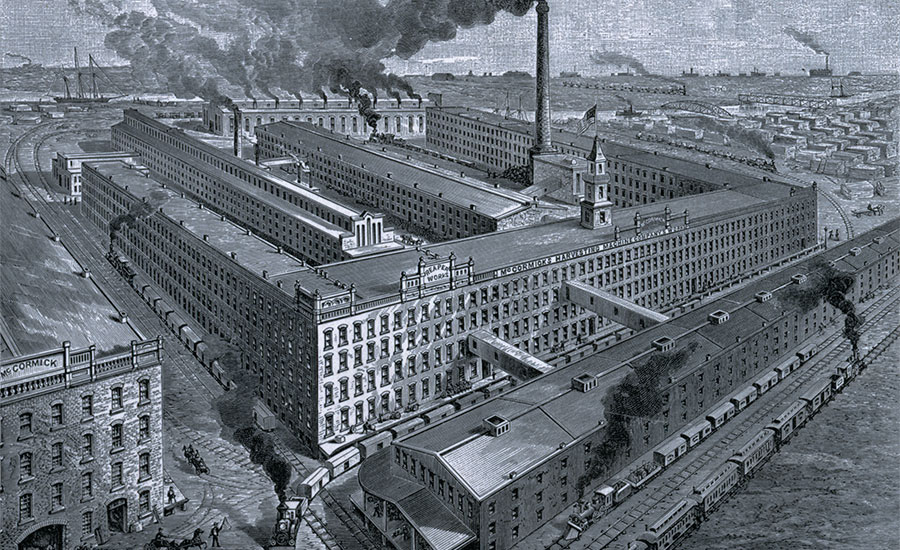

The new McCormick Works opened on the Southwest Side of Chicago in 1873. It eventually grew into a 90-acre facility that featured 45 buildings and employed thousands of people. Illustration courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

The McCormick brothers ended up being in the right place at the right time. During the small factory’s first full year of production in 1848, several other momentous events occurred in Chicago. The Galena & Chicago Union began operating; the Illinois & Michigan (I&M) Canal opened, linking Lake Michigan with the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers; and the first telegraph line between Chicago and New York City went into operation.

Within two years, McCormick was producing 1,400 machines annually. A few years later, the factory was lengthened from 100 to 190 feet. The company also installed a 30-horsepower steam engine and added a rail spur. Soon, more than 200 employees were turning out 40 machines per day and the company occupied more than 100,000 square feet of floor space.

The McCormick Reaper Works was considered to be a modern marvel. In the early 1850s, the Chicago Daily Journal newspaper profusely described its operation this way:

“An angry whirr, a dronish hum, a prolonged whistle, a shrill buzz and a panting breath—such is the music of the place. You enter—little wheels of steel attached to horizontal, upright and oblique shafts, are on every hand…Rude pieces of wood [arrive] upon little railways, as if drawn thither by some mysterious attraction. [The lathes] touch them and presto, grooved, scalloped, rounded, on they go…The saw and the cylinder are the genii of the establishment. They work its wonders, and accomplish its drudgery…Below, glistering like a knight in armor, the engine of 40 horse power works…silently…shafts plunge, cylinders revolve, bellows heave, iron is twisted into screws like wax, and saws dash off at the rate of 40 rounds a second.”

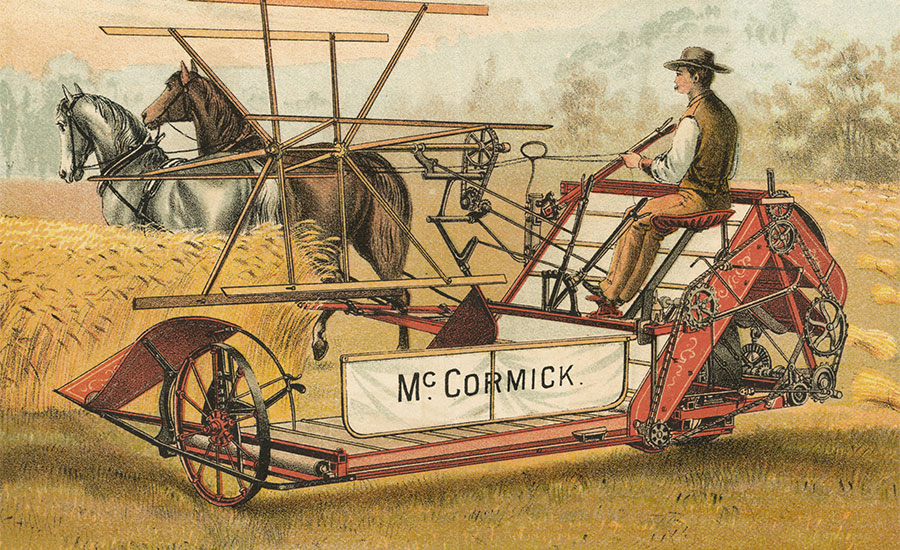

McCormick’s reapers and mowers were pulled by horses until tractors became popular in the 1920s. Illustration courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

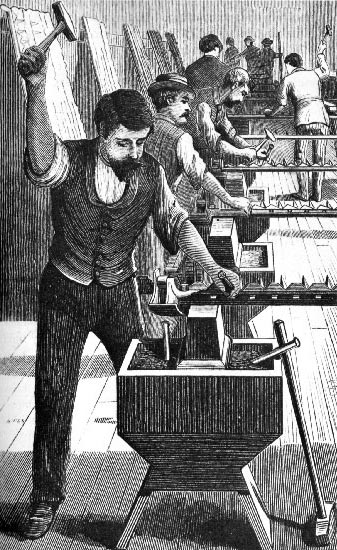

Despite that gushing praise, McCormick’s early production techniques were somewhat backward and primitive. The company relied heavily on artisanal craft methods and traditional tools used by blacksmiths.

“Leander’s reliance on cast iron and cast malleable iron dictated against the use of drop-forging equipment, one of the hallmarks of New England armory practice,” says David Hounshell, author of From the American System to Mass Production, 1800-1932. “Not until the early 1880s is there any mention of drop-forging at the McCormick works.

“McCormick’s machinery [was] entirely different from the highly specialized machine tools that characterize New England armories and the American system of manufacturing,” adds Hounshell. “Virtually absent [was] a rigorous gauging system whereby every critical dimension is checked. Completely absent [was] a rational jig and fixture system.”

To keep up with demand and boost productivity, the McCormick brothers regularly enlarged and improved their factory, which was designed with ready access to water and rail transportation so that mass production could easily tap into mass distribution. The facility was built to control costs and was strategically situated between docks on the Chicago River for receiving raw materials, such as lumber, and railroad tracks for shipping finished products.

McCormick originally relied on suppliers in New England for parts such as blades and sickles, but it gradually developed a network of local Chicago firms for metal castings and other components. In 1849, the company estimated its manufacturing cost to be $55 per machine. However, as McCormick grew in size, it became more centralized and vertically integrated.

By 1859, when reaper production surpassed 5,000 units annually, the factory was operating five woodworking shops and a foundry.

Eventually, McCormick expanded beyond reapers to include other horse-drawn farm implements, such as corn and wheat binders, hay and grass rakes, and sickle mowers. Most of the devices were made from hundreds of metal and wood parts.

Iron and steel were used for components such as axles, cutting blades, gears, shafts and wheels for durability. Chassis, frames and bodies were made out of wood, which was readily available in Chicago’s burgeoning lumber district.

To generate demand for its products, McCormick pioneered a variety of sales and marketing techniques, such as advertising, paying on credit and try-before-you-buy tactics. The company also waged a series of drawn-out patent wars with competitors.

The McCormick Reaper and Mower Works was the largest factory in Chicago by 1868. That year, the facility turned out more than 9,500 machines. Business continued to boom until October 1871, when disaster struck. After a long, dry summer and fall, Chicago became engulfed in a wild fire that destroyed large swaths of the city, including the reaper works.

Bigger and Better, But Bitter

After the fire, the McCormick Works was built on the Southwest Side of Chicago in the Canalport neighborhood, near the eastern terminus of the I&M Canal. When it opened in 1873, the facility was bigger and better than ever. It featured five-story brick buildings and a 300-horsepower steam engine. The 23-acre complex eventually grew into a huge facility covering more than 150 acres, with numerous buildings that employed thousands of people.

Because of the new facility, McCormick Harvesting Machinery Co.’s production doubled between 1870 and 1880. By 1879, the company was producing 18,000 machines a year at an average cost of $29 each. But, production techniques remained rather primitive.

“Until about 1880, the McCormick Works in Chicago depended primarily upon blacksmiths, skilled machinists and skilled woodworkers to build its reapers,” says Hounshell. “From the beginning of the business, Cyrus McCormick’s younger brother, Leander, was responsible for the production of the reaper.

Until the early 1880s, McCormick relied heavily on artisanal craft methods and traditional tools used by blacksmiths. Illustration courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

“Leander, whose only experience had been as a country blacksmith from Rockbridge County, VA, operated the reaper works as though it were a large country blacksmith shop,” explains Hounshell. “Rarely did he draw upon the stock knowledge about large-scale manufacture that had developed in New England, and even more rarely did he use the special tools devised there or the New England concepts of specialization of machine tools.”

Leander was eventually ousted from the company in 1880 after a bitter fight with his older brother (according to some historians, he was jealous of all the praise and attention that Cyrus received as being “the father of modern agriculture” and the person “having done more for agriculture than any living man.”). He was replaced by an engineer who previously worked at the Colt gun factory and the Wilson Sewing Machine Co. in Connecticut.

Lewis Wilkinson convinced upper management that drastic changes in the factory were necessary, including the importance of part interchangeability and standardization based on a system of models, jigs, fixtures and gauges.

“This event brought an end to the blacksmith-machine shop-carpenter shop approach to reaper manufacture and signaled the beginning of production under the American system of manufactures,” claims Hounshell.

Wilkinson made numerous changes, such as adding a night shift at the McCormick Works to boost productivity and bringing more order and discipline to the factory floor. “For the first time in the company’s records the words ‘gauges,’ ‘pattern machines’ and ‘jigs’ consistently appear,” says Hounshell.

However, all of those changes were not popular with workers, which lead to labor unrest and instability.

“Without question, there were certain costs to…the institution of a new system of manufacture,” notes Hounshell. “Labor problems ranked foremost. The net result of the changes initiated by Wilkinson…was that the company gained increasing control of work processes from skilled workmen….This series of changes in approach to production between 1880 and 1894, which offered a sharp break from the past, played a fundamental role in the ‘prelude to Haymarket.’”

In 1880, Cyrus McCormick died and his son, Cyrus Jr., took over management of the company. During the next four years, the factory became more mechanized and annual production volume rose dramatically from 21,555 machines to 54,841 units.

“McCormick City,” as it was referred to by some locals, employed 1,400 workers by 1884. The complex also became more vertically integrated, producing nearly every part used in its machines, including cotter pins, nuts and bolts.

Labor unrest reached a boiling point in 1884 as workers staged a bitter strike. Two years later, the company installed new pneumatic molding machinery to replace skilled iron molders and their powerful union. However, the machines produced poor quality castings and led to a labor revolt, including several strikes.

On May 3, 1886, a long-simmering strike at the McCormick Works erupted in violence. Police used brutal tactics to defend non-union workers from attacks by strikers as they left the factory. Unfortunately, they fired on the crowd, killing several people.

That incident led to a large protest rally the next evening in Haymarket Square on the West Side of Chicago. Someone in the mob, which included anarchists and socialists, threw a home-made bomb that killed eight police officers and injured 60. An undetermined number of bystanders were also killed or injured.

This view from 1900 shows how mowers were assembled at individual workbenches before the advent of conveyors. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

Manufacturing Marvel

After many labor issues were resolved, the McCormick Works thrived in the late 19th century. The success of the operation also attracted other farm implement manufacturers to Chicago, such as William Deering, who eventually set up a huge reaper works of his own along the north branch of the Chicago River. In 1902, Deering merged his company with McCormick and several other rivals to form International Harvester Co.

An article in the September 1915 issue of The Harvester World, a company magazine for employees, described the McCormick Works as “126 acres of land in the heart of Chicago covered by five-story factory buildings, electric power stations, forges and foundries…alive with…flying belts, whirling pulleys, giant wheels and thundering drop hammers. Imagine all this city of steel, fire and thunder beating rhythmically with a giant unity, and you have a faint picture of the largest farming machine factory on earth.”

By 1920, the McCormick Works was bigger and better than ever. Its 160 acres of multistory buildings were the equivalent of “a one-story building 25-feet wide and 30 miles long,” boasted a visitor guidebook from the period that contained 76 pages describing the inner workings of the facility.

“It is now the oldest and largest harvesting machine plant in the world,” claimed the publication. “Neither words nor photographs can fully represent so vast an aggregation of factories, foundries and workshops. Driven by seven great engines, operated by 7,000 employees, this immense industrial mechanism packs 14,000 freight cars with its finished product in a single year.”

In addition to a huge foundry, machine shops and assembly lines, one of the most impressive features of the McCormick Works was a twine mill that occupied 500,000 square feet and produced 30,000 tons of material per year. Workers processed it completely from raw fiber into packages of balled twine that was used with wheat binders and other types of farm equipment.

The company eventually became even more vertically integrated. It owned a steel mill on the Southeast Side of Chicago, coal mines in Kentucky, iron ore mines in Minnesota, and forests and sawmills in Missouri. Raw materials were transported by a fleet of ships and several short-line railroads owned by the company.

Vertical integration enabled the company to boast in the mid-1920s that “mowers [will emerge from the factory] three hours and thirty minutes after the pouring of the molds in the foundry.”

Progressive frame assembly relied on small circular tracks and carts that were manually pushed from workstation to workstation. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

To increase throughput, the McCormick Works adopted production techniques that were pioneered in the auto industry. For instance, it implemented “progressive assembly” processes to make binder frames. The complex also featured a variety of chutes, slides and conveyors that processed and fed the 3,800 parts needed to assemble a binder.

“You cannot take a dozen steps in the McCormick Works without coming upon some one of the countless huge, ungainly looking machines that do their work with the nicety and precision of a high-priced watch,” proclaimed an article in the June 1917 edition of The Harvester World.

“At the McCormick Works, wherever machines can be made to do the work as well or better and more speedily than men, they are used. Where the work is such that it must be done by hand, every effort is made to systemize it and eliminate unnecessary steps.

“Progressive frame assembly is carried on within small circular tracks laid on the floor surrounding a space 30 feet in diameter. Each track is covered with small trucks, waist high. Binder frames in their very beginning start at one point on this track, moving along, growing step by step to come off as finished frames when they have completed the circuit.

“The men work inside the circle, each one having a certain part to attach. Each man takes the part from a truckload which always stands at hand, assembles it and pushes the truck on to the next man. The last man on the circuit hangs the frame up to be carried away by an overhead trolley.”

Tractors and Torpedoes

In the early 1900s, engineers at International Harvester began experimenting with internal combustion engines. The company’s first line of tractors appeared in 1908. Its big breakthrough, the Titan, helped usher in a new era in agriculture.

To meet growing demand, a Tractor Works was constructed next to the McCormick Works. More than $1 million was invested in the state-of-the-art facility, which even included a test track. By 1910, half of the 4,000 gasoline-powered tractors built in the U.S. rolled out of the complex.

A decade later, the 49-acre Tractor Works comprised 17 buildings and 850,000 square feet of production space. And, productivity soared after engineers installed a moving assembly line.

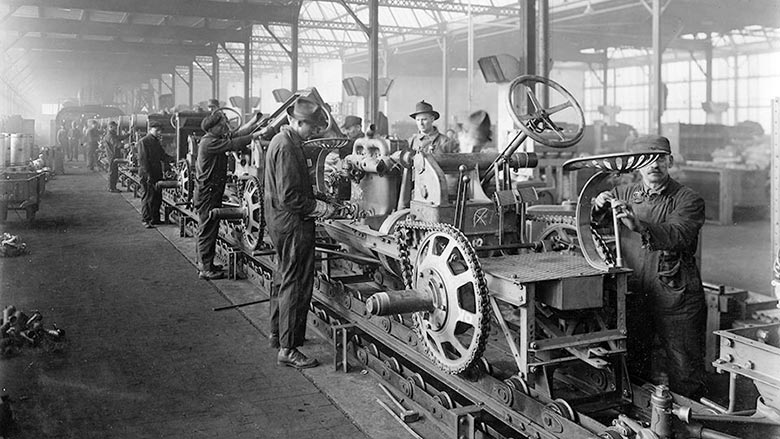

The moving assembly line dramatically changed manufacturing operations at the McCormick Works. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

“One-at-a-time days gone at Tractor Works,” proclaimed an article in the May 1923 issue of The Harvester World. “Upon the completion a short time ago of the installation of several hundred thousand dollars’ worth of new equipment…of 507-foot and 250-foot progressive assembly conveyor chains and of numerous other innovations and adaptations of personnel and equipment, Tractor Works is entering upon another major period of progress in tractor manufacture.

“Every operation, every inspection, every movement consumes the least time at the least cost, without sacrifice of quality or uniformity. Progressive assembly and quantity production in the full sense of the latest engineering practice now entitle Tractor Works to rank among the leaders in this type of quality-quantity manufacturing.”

By the end of the 1920s, those investments paid off. International Harvester produced 60 percent of the tractors built in the U.S., including the popular Farmall and McCormick-Deering brands.

An article in the October 1930 issue of The Harvester World described the Tractor Works as a modern marvel of manufacturing. “[After engines are assembled and tested, they] finally are lined up to feed the main tractor assembling line. Further along, transmission and drive gears, which have been developed in a large department of their own, are put into position, and so on with the other components.

“The massive tractor main frame, milled by rotary cutters, and drilled and tapped in a remarkable machine operated by one man, is the first part hoisted on to the slowly moving assembly track. As it proceeds, its components are added to it in order, by men who are experts in their particular fitting operations, so that each part literally slides into its prescribed location without the smallest hitch.

“When the endless chain conveyor gets as far as the tunnel-like paint booth, the tractor is complete except for its wheels. It enters the booth, paint is sprayed on by compressed air, and when it emerges the separately painted wheels are fitted. The complete tractor then makes a journey through the 35 yards of the drying tunnel, at the end of which it receives the ‘pipe, tobacco and matches’ of locomotion—petrol, oil and water.

“When it is just ready to roll off the production line, the engine is started up and as soon as the wheels make traction with the floor, the machine is driven away under its own power.”

During World War II, the McCormick Works assembled thousands of aerial torpedoes for the U.S. Navy. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

During World War II, both the Tractor Works and McCormick Works played key roles in the “arsenal of democracy.” The former mass-produced military bulldozers for the U.S. Army, while the later made Mark XIII aerial torpedoes for the U.S. Navy.

Each torpedo weighed more than 2,000 pounds and was 13 feet long and 22 inches in diameter.

“The torpedo is unlike anything [we have ever] manufactured before,” claimed at article in the July 1943 issue of The Harvester World. “We never have built any product where the tolerances throughout are as close as in the torpedo. Indeed, few products ever have been built by mass production methods where the precision required was so great.

“The torpedo work is as fine as the finest watch or compass. It would be difficult to name any product in which there are so many small, delicate parts which must be machined and finished to such infinite tolerances, and adjusted to such close fittings. There are in excess of 1,000 parts in the torpedo. In the production of those parts, Harvester employees perform between 15,000 and 20,000 individual, separate operations.

“It was realized from the first that many women would have to be used for torpedo work, both because women are being called upon to perform more war jobs, and because they are more adaptable to many of the operations on the small, delicate parts that go in the torpedo.

“Some of the most difficult jobs in torpedo production are the assembly jobs on small parts. Here the problems are very similar to the assembly of a tiny wrist watch, calling for patience, precision and individual skill. Much of this sort of work must be done under a magnifying glass.

“There are parts where the accuracy must be maintained to 25 ten-thousands of an inch. Some parts are sorted within a limit of 25-millionths of an inch. There are parts which fit so snugly that a particle of dust on them will destroy the accuracy required.”

End of an Era

After World War II, International Harvester began to rest on its laurels and failed to keep up with changing market conditions. After a century at the top, it lost the coveted No. 1 market share of the farm machinery industry to Deere in 1958 and never recovered.

In 1959, IH decided to close the legendary McCormick Works. An article in the April 19, 1959, issue of the Chicago Tribune said that “a number of trends in agriculture and the farm equipment market, plus the age and condition of the plant buildings, prompted the decision….At the same time, the average size of farms has grown, creating a need for larger implements. Buildings at the McCormick Works are not suited to production of these bigger units.”

At the time 3,800 people were employed at the facility, which consisted of 53 buildings spread over 104 acres. Implements made at the site included corn, cotton and potato planters; seeders; fertilizer distributors; field harvesters; harrows; and rotary hoes.

“McCormick Works had sprung up during the era of animal-powered faming,” explained an article in the June 1961 issue of The Harvester World. “The wooden horse-drawn implements for which it had been designed were doomed with the coming of the tractor.

“In more recent decades, the trend toward fewer and larger farms has produced another major change: a swing from single- and two-row implements to eight-row. McCormick’s multistory, mill-type buildings were not suited to production of the heavier machines.”

“This plant was the wonder of its day, but manufacturing concepts have changed,” lamented Mark Keeler, vice president of the farm equipment division at International Harvester (IH). “Five-story buildings just don’t lend themselves to efficient production methods.

“A lot of our floors wouldn’t support forklift trucks. Materials had to be hand-trucked into warehouses, out of warehouses, into boxcars. There was a constant movement of little two-wheel hand trucks into elevators, up five floors and back down. And most of the elevators—we had 38—were steam powered and slow.

“Modern material handling was out of the question. We tried everything in our power to keep the plant going, but the odds were too great.

In the early 1920s, International Harvester adopted moving assembly lines from the auto industry to mass-produce farm tractors. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

“Unfortunately, the changing nature of the farm implement business and the physical problems of McCormick Works left us no choice. We couldn’t afford to manufacture in an obsolete and high-cost factory like McCormick Works when we have more efficient space at other plants.”

Production was shifted to newer, one-story IH facilities in Canton, OH; East Moline, IL; Hamilton, ON; Memphis, TN; and Waukesha, WI.

Demolition work took several years to complete, with the project wrapping up in April 1962. However, production continued throughout the decade at the Tractor Works next door. After World War II, the facility had stopped producing wheeled row-crop machines and specialized in crawler tractors. By the late 1960s, it had become an “obsolete and uneconomic plant” and fell victim to a cost-cutting initiative.

By the time the last machine rolled off the line in 1969, the Tractor Works had assembled more than 3 million vehicles. Production was moved to newer, one-story IH facilities in the Chicago suburbs of Libertyville and Melrose Park, IL.

During the next decade, the grand dame of Chicago manufacturing experienced a downward spiral, withering away until finally succumbing to changing business conditions in the wake of a bitter strike in the late 1970s. Remarkably, a member of the McCormick family (Brooks McCormick, the great grandnephew of Cyrus) was still running the company up until 1980.

The IH construction equipment division was sold to Dresser Industries Inc. in 1982 and the agricultural machinery division was sold to Tenneco Inc. in 1985. The medium- and heavy-duty truck division (created in 1917) was spun off into Navistar International Corp. (acquired by Volkswagen AG’s Traton division in 2021).

Today, the IH name lives on as part of the Case IH division of CNH Industrial, which was acquired by the forerunner of Stellantis in 1999. The McCormick name was resurrected in 2000 for a popular line of farm tractors that are currently made by an Italian company called ARGO.

The IH tractors and implements that once rolled out of the company’s large factories in Chicago are now highly prized by collectors. Many have been restored to like-new condition and are a popular site at country fairs and vintage vehicle shows.

To view additional photos of International Harvester's assembly lines and learn more about other factories that made Chicago a production powerhouse, see Made in Chicago: The Windy City’s Manufacturing Heritage.