Automakers, suppliers, universities and government labs around the world are scrambling to develop self-driving vehicles. In fact, Nissan is currently building a “dedicated autonomous driving proving ground” in Japan. When it opens later this year, the facility will feature real brick-and-mortar townscapes that will be used to push vehicle testing beyond the limits possible on public roads.

According to a recent report by Navigant Research, sales of autonomous vehicles will skyrocket from fewer than 8,000 annually in 2020 to 95 million by 2035, representing 75 percent of all light-duty vehicle sales.

Advanced drive-assistance features have been available in the luxury vehicle market for some years, but a notable advance came in 2012 when functions such as adaptive cruise control and lane-departure warning were offered on standard cars for the first time.

“Combinations of these features are now being brought to market in some 2014 models to offer semiautonomous driving,” says David Alexander, senior research analyst at Navigant Research. “Increasing volumes and technology improvements mean that it is now feasible to install the multiple sensors necessary for such capability, thanks to cost reductions.”

Significant hurdles still remain, but those obstacles are not technological. “Advances in computing power and software development mean that features such as high-end image processing and sensor fusion are now ready for production,” says Alexander. “The factors that remain to be solved before rollout to the public are those of liability and legislation.”

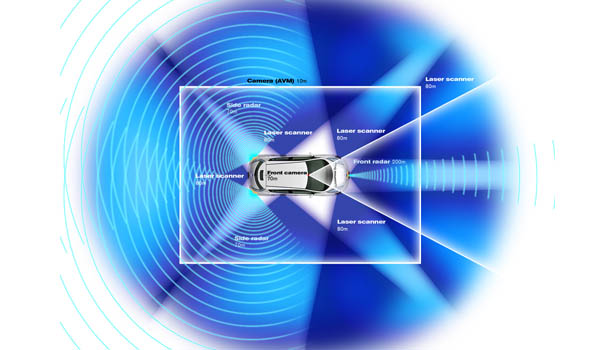

Driverless vehicles will depend on a wide variety of onboard components, including radar, lidar, satellite navigation systems and cameras, plus a slew of sensors that measure things such as wheel speed and yaw rate. That opens up lots of new challenges and opportunities to engineers.

“Many components, such as cameras, are already being shipped in reasonable volumes,” says Ian Riches, director of the global automotive practice at Strategy Analytics Inc. “The highest-cost sensor used at present in development vehicles is the Velodyne lidar sensor that [sits atop a vehicle and rotates]. This is too large and bulky for mass-market deployment. And, with a $70,000 to $80,000 price tag, it’s also way too expensive.”

Several companies are currently developing much less expensive and smaller devices. For example, Quanergy Systems Inc—a Silicon Valley start-up company—plans to charge less than $500 for a device that it’s developing that would be the size of two cigarette packs. Within a few years, it hopes to reduce the cost and size of the device to less than $200 and a single cigarette pack in size.

Driverless technology will also add several extra layers of complexity to final vehicle assembly. “The major extra step will be the calibration of all the various sensors,” says Riches. “They will need to be calibrated together, so that they provide [reliably] consistent information. [Otherwise, they may detect] two obstacles where there is only one, or vice versa.

“In the very long term, however, these systems could make vehicle assembly less complex and costly,” notes Riches. “A lot of effort today goes into making vehicles perform well in impact tests. If autonomous technology makes car crashes a thing of the past, then a lot of [traditional restraints would be eliminated].

“Lighter, thinner materials could be used,” Riches points out. “Different packaging concepts could be explored if protecting the driver and passengers from impact is no longer such a [critical] consideration. Restraint and protection systems, such as seatbelts and airbags, could be radically rethought or eliminated all together.

“But, we’re a long way from that at the moment,” warns Riches. “For the foreseeable future, a driver will need to be present and ready to step-in should circumstances dictate. That means that there will need to be a full set of controls that the driver is familiar with, such as a steering wheel and a brake pedal.”